The following is a musing, albeit limited, on some elements of an additional critique coming from a Christian background.

Ever since the British colonisation of Australia, governments have concentrated on the security of our borders. This has often been done with very little mercy or compassion.

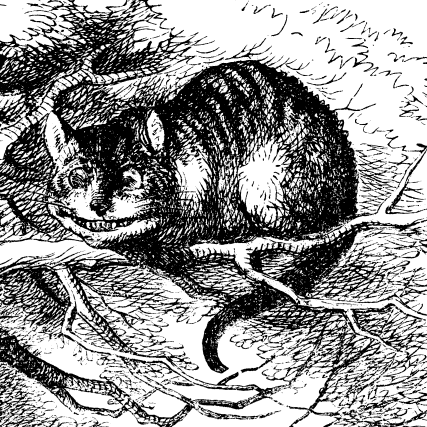

In Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice asks the Cheshire Cat which way to go, to which he replies: “That depends a great deal on where you want to get to.”

“I don’t much care,” says Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go.”

“So long as I get somewhere,” Alice adds.

“Oh you’re sure to do that,” says the Cheshire Cat, “so long as you walk long enough.”

I believe most of us, as Australians, do care what road we are on and what destination we have as a result. Sometimes we describe this as giving everyone ‘a fair go’ or being decent global citizens. I would add assisting those on the edges of society and, in the context of refugee policy, giving people damaged by trauma as much help as we can to turn their lives around.

Legislation is one thing, but the human face of the people seeking protection offers a compelling case for concern. Except for chance, any person could be a refugee. Some of us are incredibly lucky to have been born in a free and affluent country like Australia. Others share none of this good fortune. Most of those who come to BASP worry incessantly about their future, how they can live, and where their future will be lived out. They have put so much hope in this country they thought would be a great nation for them.

If we want a litmus test for how decent we are (individually, nationally or globally) I believe we should look at how we treat ‘the Other’. This is particularly so when the Other is vulnerable and marginalized. Our logo for the Brigidine Asylum Seekers Project has the words ‘I was a stranger and you made me welcome’. Refugee is our modern equivalent word for the word stranger in the bible. We believe that part of being truly human means learning how to welcome the stranger.

The latest anti-refugee bill, as well as others passed late last year, reminds us forcibly that, as a community, we need more reflection on whether we have societal values that can help us articulate why we find this legislation so unacceptable. If so, what are these? What are the elements of public morality that help us grapple with communal issues such as the displacement of people who then seek protection in Australia? The cult of individualism, fostered in western society, often only extends to answering, “How does this affect me?” Many Australians are not satisfied with this.

Human beings are migrants. For centuries history attests to the establishment of artificial borders that separate peoples, usually a result of war, mass killing and destruction and then the reality of people fleeing for their lives. These borders can be opportunities to extend hospitality to the disenfranchised or be places where ‘the Other’ is treated with violence and cruelty. More often than not, they become boundaries that are used to exert power and keep the vulnerable out. From a Christian point of view, there is a moral duty for every country to regulate its borders with justice and mercy. There will always be controversy about what this looks like.

This is not a new issue. The Israel of Jesus’ time was controlled by the Roman Empire. Both the Romans and the Jewish leaders had social structures and laws that had been erected by the powerful to maintain their privilege. Jesus’ simple act of healing a man on the Sabbath sets into motion the Pharisees’ plot to kill him. For much of human history, compassion for the excluded has been, in itself, a confrontation with the powers of the day, calling for a radical act of justice.

Much of biblical literature grapples with the question: What is good, who is a good person, what is a good way of life? One such passage is in Matthew’s gospel and is known as the Beatitudes. These read like a list or a collection of things (like proverbs) handed down by the small group of Jesus’ followers. Basically, Jesus is saying that in his vision of a decent and good world (the kingdom) you will not be excluded because you are poor, persecuted, and hurting. Indeed, if you are merciful, kind and trying to achieve justice and peace then you are the sort of person who fits his view of a new world order, what he often called the Kingdom. The Beatitudes offer a critique not just of Jesus’ time but also of our own. This is uncomfortable stuff.

In Jesus’ time the ordinary people were being oppressed, not just by the Romans, but also by their own corrupt religious and political leaders. This was a very stratified society, where all the rules and laws favoured those in power. And Jesus was a layman from a disreputable province, ready to challenge the swindling and oppression he saw from those in authority. He was an itinerant preacher, a voice for the powerless ones – the sinners and prostitutes, lepers, demoniacs. Beggars, those diseased, crippled, hungry and widowed.

In a world where vengeance rather than justice was the norm, the ones seen to be blessed in Jesus’ new kingdom was extraordinary. They were often people from outside Israel and therefore seen as infidels.

One of the strongest messages from the gospels and the message of Jesus is a call to mercy (a loving disposition). Jesus promises that those who show mercy will be shown mercy. It is an ethic of reciprocity that Jesus often comes back to. Mercy involves entering into a situation, a relationship with someone, going past the rules and the easy stock answers which protect us from taking responsibility for the pain such decisions cause.

The story of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37) indicates that mercy transcends social and religious boundaries. The Canaanite woman who is from another race and therefore an outsider (Matt 15:21-28) does not immediately get Jesus’ attention as she begs him to cure her daughter, but he responds to her plea for mercy.

If Christians are to pay more than lip service to being disciples of Jesus, a challenge is to model accepting every human person as worthwhile and not putting a higher ranking on some persons than others – whatever their worthiness, race, sex, religion or class. Jesus was critical of teaching the letter of the law rather than its spirit. He taught the difference between law and life, justice and love. His emphasis was always on forgiveness. The ultimate failure in his eyes was Pharisaism.

In Jesus’ day the voices of the strangers (refugees) were silenced because they had no status in society. In the first testament there are many allusions to the strangers: “You must not pervert justice in dealing with a stranger or orphan nor take the widow’s garment in pledge”; “Remember that you were a slave (did not belong) in Egypt and that Yahweh your God redeemed you.”

This wasn’t new in the biblical story. Deuteronomy emphasizes what the ‘people of God’ should do and how they should live. Yahweh is committed to justice and indeed is defined by justice. The message from the early books in the bible is that if we want to be like God we need to be just: “When you are harvesting your crops and forget to bring in a bundle of grain from your field, don’t go back to get it. Leave it for the foreigners, orphans, and widows.” (Their only sustenance was to come along already harvested land and try to get any grains left.)

So how is biblical justice different to justice as we often use the concept? Above all else, Jesus teaches that each human being, including the most unattractive and unbelieving, is precious and must be treated as a brother or sister. He ate with tax collectors and sinners rather than the “good” people he could have chosen. (Matthew 9:9-13).

We pride ourselves on being a country where the rule of law prevails. To signify this, we have the blindfolded lady holding the scales, found outside law courts. The image conjures up weighing evidence, stressing impartiality, avoiding bias. Biblical justice is different. Jesus opts for justice tempered by mercy which is swayed in favour of the poor, opts for a bias for the outsiders and the sick and mentally disturbed. Biblical wisdom would take off the blindfold and see who is tampering with the scales. Biblical justice does not claim to be impartial. It is interested in how status, gender, class and race is making a difference.

Asylum seekers are usually outsiders – with mental and physical health issues, lonely, poor and excluded from many of the services available in mainstream society. Shipping them off to Nauru does not fit this kind of justice. It does not include much mercy or compassion.

Alice asks the Cheshire Cat, “Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?” We could ask the same question of our attitude to people seeking Australia’s protection.